Designing the Token Specification

written by Jake Fenton

In this post I shall document the saga of my developing a token structure for the preprocessor.

I’ll be heavily referencing the GNU C Preprocessor specification–specifically section 1.3 on tokenization–throughout this post (which I have an offline copy of thanks to wget).

Wait, what’s a token?

Ah yes, this is supposed to be a cold-start guide to writing a preprocessor.

(Again, disclaimer that some of this is possibly wrong–While I did take a compiler course I was on the ‘student’ side of the interaction, and I do not claim to be an expert on compilers.)

In the general sense, a compiler is a system for translating a language. Languages have an alphabet from which symbols can be arranged in ways that have meaning. Tokenization is the process of taking a stream of these symbols, grouping them and classifying them. Tokenization acts only on the symbols–it doesn’t determine grammar, necessarily.

Take this basic example of a math equation:

y = 5 x + 17

We might tokenize thusly, where [] denotes a token:

[variable, y] = [number, 5] [variable, x] [operator, +] [number, 17]

This stream of tokens will later be fed to a parser which is responsible for building the abstract syntax tree which is what will actually describe how these tokens interact with each other.

But that’s a topic for later–right now we just need to break apart some c++ code into tokens, which means we get to learn regex!

Wait, what’s a regular expression?

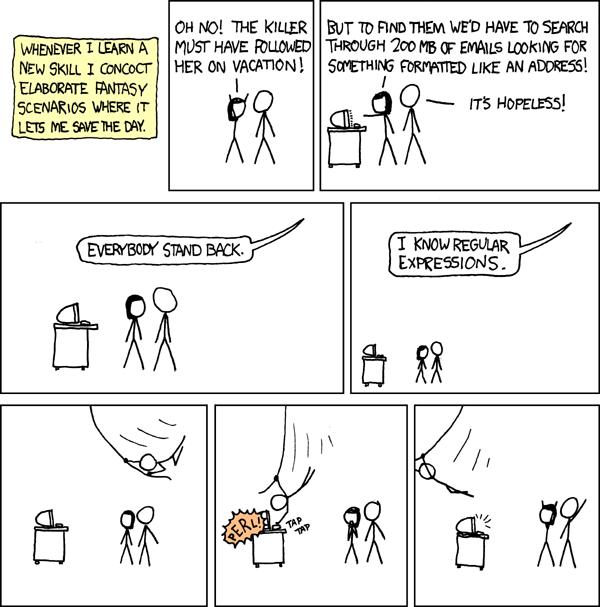

Regular expressions are hands-down my favorite part of my compilers course.

A regular expression is a way of describing a pattern that would get used in something like grep or the find-and-replace dialogue. I think the best way to learn them is by seeing them and then experimenting. I highly recommend the site regexr as a resource for learning.

We’ll use regular expressions to define what our tokens can look like. Within our lexer (the thing responsible for building the token stream from the input stream of the language) regular expressions will be transformed into a set of finite state machines, which will be used to figure out what the input could match.

Anyway, back to tokens.

(chunks of this will just be me regurgitating the aforementioned GNU page)

According to the GNU reference pages, from the preprocessor’s view there are five categories of tokens we care about:

- identifiers

- preprocessing numbers

- string literals

- punctuators

- other

An identifier is what you would expect–anything that could also be an identifier in C/C++; starting with an underscore or letter, and then alphanumeric with underscores throughout. The regex for this would look something like:

[_a-zA-Z][_a-zA-Z0-9]+

A preprocessing number includes the normal integer and floating point numbers that you can use in C but also includes a weird format of numbers that will make for a very ugly regex; the formal specification requires an “optional period, a required decimal digit, and then continue with any sequence of letters, digits, underscores, periods, and exponents.”

“Well that’s not so bad,” you say. “What’s so hard about that?”

The exponent can be any of ‘e+’, ‘e-’, ‘E+’, ‘E-’, ‘p+’, ‘p-’, ‘P+’, or ‘P-‘.

So, I’m going to attempt to sketch out an example regex of what that might look like:

\.?[0-9]([0-9]|(e\+)|(e\-)|(E\+)|(E\-)|(p\+)|(p\-)|(P\+)|(P\-)|[a-zA-Z])*

Note that the character class [a-zA-Z] has to come AFTER the definition of all of the exponent groups, or the regex will count the leading character of the group as a letter and not an exponent.

According to the magical GNU document, this weird definition is to “isolate the preprocessor from the full complexity of numeric constants.” Initially, I thought this was ridiculous, as we would have to somehow determine if the number was valid or not before using it in operations, and then I remembered that it’s not our job to do that, as we just build tokens, occasionally expand things, and pass the lot of tokens onto the compiler.

(This is something I’ve been quite bad about, actually, is remembering how limited our responsibilities are. I’ll have to work on being better at that.)

String literals are pretty much what you’d expect. One thing to note is that arguments to #include are technically string literals.

Quoting from the magical GNU document again, “There is no limit on the length of a character constant, but the value of a character constant that contains more than one character is implementation-defined.” Again, though, it’s probable that we won’t have to concern ourselves with that as it will fall to the compiler. That said, the fact that the GNU document notes this is suspicious, as the document is exclusive to the preprocessor.

My sketch of a regex for string literals is:

('|")((\\['"tn])|[^'"\\])*\1

Punctuators are the standard set of puncutation meaingful to C and C++, which I looked up in the C++ specification doc I have:

If we ignore the keywords that C++ cares about (bitor, etc), which will be read as identifiers to the preprocessor, and the concatenations of other operators, and digraphs and trigraphs, it’s a pretty normal set of punctuation.

And of course, my regex sketch:

[{}:;,?%&*<>=/!]|[\[\]\(\)\.\^\-\|\+]

Next Steps

So, now that all the tokens are skethed out we’ll just need to define some test cases for the broad token types and see if we can correctly parse them. If/when that happens we’ll break the tokens down into what the preprocessor actually cares about, and then attempt to act on them.

Once we can handle lexing the incoming files we can work on the actually hard problems like passing the tokens to the compiler, including files and other fun stuff.